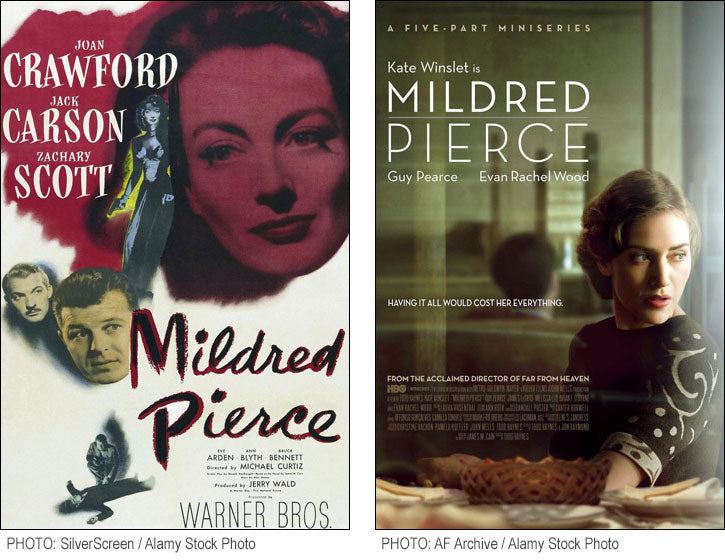

Now that we need more entertainment and diversion in our lives, streaming services have been increasing their offerings. Lucky for me – I’ve finally seen the 2011 HBO mini-series Mildred Pierce. As I found out upon my recent viewing, it couldn’t be more different from the 1945 film I’ve enjoyed seeing countless times. Two productions based on the same James M. Cain novel have essentially the same plot, but that’s where the similarities end. Before I can tell you about the jewelry, I have to set the scene by first talking about the book, the two productions, and Mildred Pierce’s costumes.

The Novel

Published in 1941, Mildred Pierce is unlike the author’s previously successful novels. Instead of a hard-boiled crime story, this one has been described as “social realism in its attention to the detail of its heroine’s day-to-day existence. At the same time, it has features of romantic melodrama and is relatively frank about sex.” (Cook 380).

Set in Glendale, California, during the Depression, Cain tells the story of the title character over a ten-year period, starting in 1931. The mother of two daughters and the wife of an unemployed, unfaithful, failed property developer, Mildred bakes cakes and pies to sell to neighbors to support her family.

After throwing out her husband (Bert) and finding work as a café waitress, she struggles with issues of pride, social class, and the demands of her snobbish, social-climbing elder daughter. Mildred opens her own restaurant and then a chain of eateries in addition to a pie business. She works to give her daughter, a gifted singer, the best of everything, but Veda is never satisfied.

Meanwhile, Mildred becomes involved with and later marries Monty Beragon, a parasitic, penniless socialite from Pasadena (the right side of the tracks). Although she doesn’t love him, he can introduce Veda to the lifestyle and social standing she craves. As Mildred’s business and financial success grow, so do their demands. In the end, she is betrayed by both.

The 1945 Film

The screen adaptation of Cain’s novel underwent significant changes on its road to movie theatres. Because of the Hollywood Production Code censors and other issues, Warner Brothers turned the story into a murder investigation set in the early-1940s. The film “contained elements that fit perfectly into the emerging film noir mode, films of cynicism, sexuality, and greed” (Garrett 287) and used the low-key lighting and dark shadows of the genre.

Directed by Michael Curtiz, the film opens with the murder of Monty (Zachary Scott). At the police station, Bert (Bruce Bennett) is named the prime suspect. In an effort to convince the detective that her ex-husband is not capable of the crime, Mildred (Joan Crawford) tells their story.

It begins four years earlier, on the day the couple separated. The events are unfolded in flashback, ending with what happened after the 18th birthday party for Veda (Ann Blyth) held earlier that evening.

Considered “box-office-poison” by MGM, Crawford left that studio for a contract with Warner Brothers that gave her script approval. She waited two years for a suitable part. Her performance in Mildred Pierce won her an Academy Award – which she received at home, due to “illness”– and recharged her career.

The 2011 Mini-series

Todd Haynes’ production of Mildred Pierce for HBO is not a “remake of the film but an adaptation of the novel” (Cook 378). His script, written with Jon Raymond, follows the book closely in both plot structure and dialogue, with much of the latter used verbatim. The sex scenes alluded to in the novel are explicit in the series. Shot in a naturalistic style, the visuals are softer with muted colors. The cast includes Kate Winslet (Mildred), Brían F. O'Byrne (Bert), and Guy Pearce (Monty). Evan Rachel Wood plays Veda as a young woman.

The story starts in 1931 and continues for a period of nearly ten years, told on the screen in five-and-a-half hours. The viewer is steeped in the realism of life during the Great Depression and Prohibition. Amidst the backdrop of period cars, food, décor, music, and costumes, we see throngs of people on the sidewalks – many selling apples and others holding “work wanted” signs – where Mildred walks for days on blistered feet looking for a job. We accompany her to the grocery store, where she carefully counts out her available change to buy food and has to put back a package of hot dogs.

The mini-series received 21 Emmy nominations and won in five categories: Lead Actress (Kate Winslet) and Supporting Actor (Guy Pearce), as well as Art Direction, Casting, and Music Composition.

Mildred Pierce Costumes & Jewelry

Film scholar Stella Bruzzi aptly describes the different approaches to costume design for the two productions: “whereas in Curtiz’s film the costumes dress the star, in Haynes’s version they dress the character” (Bruzzi 397). Let me explain.

Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford’s “look” had been well-established by MGM’s Adrian – padded shoulders, nipped-in waists, slim skirts – by the time Milo Anderson designed the costumes for this film. What’s interesting is that its flashback framework of storytelling particularly suited Anderson’s philosophy.

Joan Crawford’s “look” had been well-established by MGM’s Adrian – padded shoulders, nipped-in waists, slim skirts – by the time Milo Anderson designed the costumes for this film. What’s interesting is that its flashback framework of storytelling particularly suited Anderson’s philosophy.

Because he thought that mood was critical in clothes, he always worked “extra hard to get a good ‘entrance’ costume so that the player will get off to a good start with the audience when they first see her” (Dempsey 22). When we meet Crawford the first time, she is wearing a bead-embellished dress with matching gloves and handbag as well as a fur coat and hat – an outfit that exudes social status and wealth.

As she tells the beginning of her story, we see her in “ordinary clothes”– a simple dress with spread collar and flowered apron while baking at home, a trench coat covering a skirt and blouse the day she found a job, her gingham-checked waitress uniform. But her wardrobe quickly improves. On the opening night of her restaurant, she wears an elegantly-tailored black two-piece dress with a long white scarf. As her success in the business world grows, she transforms into a strong, sophisticated woman dressed in her typical silhouette.

This masculine look of suits with padded shoulders was in-keeping with Crawford’s on- and off-screen style. Shoulder pads were also a fashion staple during WWII, when women took on jobs in male-dominated fields while men were at war. However, women wore prominent jewelry – often large brooches – to add a feminine touch to their military-inspired garb. Each of the star's ensembles is adorned with a brooch on her shoulder or at her throat.

Crawford was an avid collector of both fine and costume jewelry. As was common during Hollywood’s Golden Age, she and other stars often wore their own jewels. In this scene, she wears a pin-striped suit with wide lapels and a white shirt. At her throat is a gem-encrusted brooch that looks like this vermeil sterling flower brooch made by Coro for their high-end line, CoroCraft. This same jewel appears on a black blouse with a houndstooth suit in another scene.

When you watch the movie, look out for these pieces: a diamond jewel similar in design to a dazzling asymmetric sapphire and diamond pendant brooch by Paul Flato and a diamond-encrusted blackamoor brooch.

Kate Winslet

The naturalistic approach to the series’ cinematography spills over to the cast’s costumes. They were designed by Ann Roth, winner of Emmys, Tonys and Oscars for her six decades of work. In an interview with Harper’s Bazaar, Roth described her philosophy: “I don't dress movie stars, I dress actors who are playing characters … I think about how much money they spent, where they go, does she have a drawer for silk slips…”.

Roth looked to the style of the late-1920s for inspiration in the beginning episodes because “no one had any money to buy what was in the stores”. In the same Los Angeles Times article, she describes the character’s personal style as “’cautious’, defined by meek dresses and separates, ‘probably from Bullocks Wilshire [a department store]’ in the earlier years”.

When we first see Winslet in her kitchen baking pies, she is wearing a white-collared, polka-dotted dress with a gingham-check apron – an outfit not unlike Crawford’s early domestic attire. But as the story continues, “the downright frumpiness of Mildred’s excessively uninspiring costumes is noticeable, exemplified by the chocolate-coloured floral dress (with coordinating but especially unappealing cloche hat and shapeless wool coat) that she wears when looking for work” (Bruzzi 400).

When we first see Winslet in her kitchen baking pies, she is wearing a white-collared, polka-dotted dress with a gingham-check apron – an outfit not unlike Crawford’s early domestic attire. But as the story continues, “the downright frumpiness of Mildred’s excessively uninspiring costumes is noticeable, exemplified by the chocolate-coloured floral dress (with coordinating but especially unappealing cloche hat and shapeless wool coat) that she wears when looking for work” (Bruzzi 400).

Her dress for her first restaurant’s grand opening is similarly dowdy, even though it’s adorned with a triple strand of cheap-looking imitation pearls. A series of suits follow, many in linen but equally unstylish, like this one with mother-of-pearl buttons. Her character’s appearance improves gradually, but her attire is always deliberately out-of-date.

Winslet’s everyday jewelry is minimal: a wristwatch and an Art Deco-style filigree engagement ring. In some scenes she wears a three- or four-strand necklace of graduated faux pearls. These accessories are in-keeping with Roth’s vision for the character.

Her only jewelry “splurge” was on the day of her second wedding. Here we see her wearing a matching pair of wide bracelets made with what appears to be milk-glass stones with diamanté accents. Wide bracelets were prominent in the 1930s. However, these jewels puzzle me – from what I can see in the photo, they look more like a 1950s design. Milk glass and white jewelry in general were popular early in that decade.

Although Roth’s costumes for Veda are always more luxurious than Mildred’s, the outfits worn by both characters in the scene of the singer’s first big recital are extravagant. Against the “glorious backdrops” we see “the newly wealthy Mildred’s golden gown, woven with threads of real metal (Veda tends to favour the expensive two-tone fabric known appropriately enough as ‘shark skin’)” (Smith 20).

HBO donated these costumes to the Museum of the Moving Image in April 2011. Mildred’s dress is on the left; Veda’s, complete with hat and parasol, is on the right. Roth donated four related design drawings from the production. All are seen in this photo on exhibit in the Museum's core exhibition “Behind the Screen”.

Dressing the Star vs. the Character

These two productions based on the same novel illustrate how the philosophy of costume design has changed from the days of the studio system. Which do I prefer? As a jewelry lover, I have to admit that seeing Joan Crawford’s jewels is the type of visual entertainment I crave. Even without the eye candy, though, I enjoyed the realism of the HBO series. If you've seen them both, which did you like better?

For More Information

To learn more about film noir, the genre of the 1945 film, read “What is noir?” on the Film Noir Foundation's website. Eddie Muller, its founder and president, hosts TCM’s Noir Alley, which airs on Saturdays at midnight.

Quoted Print Sources

Bruzzi, Stella. “Dressing Mildred Pierce: Costume and Identity Across the Ages,” Screen, vol. 54, no.3, Autumn 2013, pp. 397-402.

Cook, Pam. “Beyond Adaptation: Mirrors, Memory and Melodrama in Todd Haynes’s Mildred Pierce,” Screen, vol. 54, no.3, Autumn 2013, pp. 378-387.

Dempsey, Lotta. “They Dress the Stars,” Chatelaine, August 1944, pp. 8-9, 21-22.

Garrett, Greg. “The Many Faces of Mildred Pierce: A Case Study of Adaptation and the Studio System,” Literature/Film Quarterly; vol. 23, no. 4, 1995, pp. 287-292.

Smith, Paul Jillian. “All She Desires,” Sight and Sound, vol. 21, iss. 8, August 2011, pp. 19-21.

1 comment

Barbara — I enjoyed this article very much and I always love your newsletters! I get to learn so much about vintage jewelry and its myriad iterations!

Leave a comment